Instagram Essays

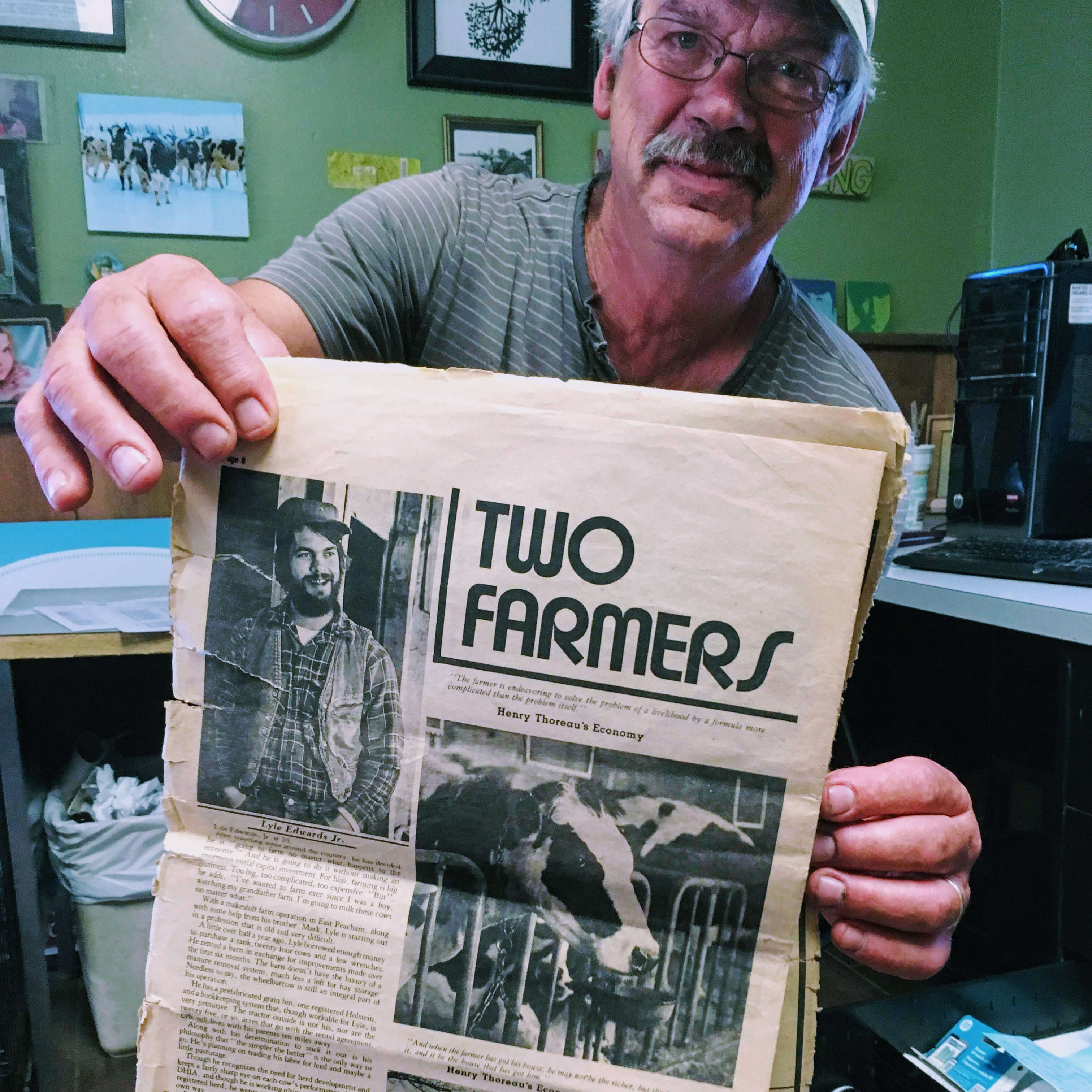

“This is me when I started in 1977.” Spud Edwards was 24 when he bought his first cows. 23 of them, farmed on a 25-acre piece of land. But Spud (a nickname — “I was a potato-eater”) had been around cows long before that, all the way back to when he ran around his grandfather’s farm as a toddler, his brown head of hair barely peeking out over the barnyard fence. “16 cows and milk cans,” he says. He pulls up a grainy photo of him and three of his siblings perched on that fence, wooden with steel hinges that his grandfather had smithed himself.

Spud now milks 50 cows on his farm in Westfield, VT, a few miles south of the border. He’s been organic for 18 years. When I meet him, he’s reading an article about the latest animal abuse exposé on a 25000-cow organic operation in Texas. “It irritates me to see that mega-dairy model coming into organic.” Organic dairying in the Northeast, as we know it today, found its beginnings right here in Vermont during the 1980s, after a small group of farmers began to reject the post-war arrival of chemical inputs. Now organic is going industrial too.

“Have you tried raw milk?” I follow Spud into the kitchen of his old farmhouse, where the afternoon light has spilled onto dark wooden cabinets and white tile.“I’ve been married, divorced and gone through the mill and started over again. I had three kids. My youngest girl died in a car accident when she was 18. I went through bankruptcy and divorce at the same time.” He turns the jug over a few times. “That’s fun,” I say. “Yeah, I had a blast.” He laughs. “No, well you know, get off the freaking floor. What do you want me to do, cry? For the rest of my life? So I just —” He pours the milk into a glass. “When I went through everything and I remarried, we rented a farm. All I had was $8000.” He bought sixteen $400 cows. That was in ’94. He hands me the glass. I take a sip. It’s sweet. “The top half of the bottle is really rich. It’s cream. My father liked that for the coffee of course. Strawberry shortcake, all that good stuff.”

(Westfield, VT | July 2019)

The Beatles are playing in Spud’s barn at 6 on Thursday morning, drowning out the steady pulse of milk pumps at work. The cows — 50 lined up shoulder-to-shoulder in two long rows — add their own erratic rhythm in splatters of poop. Spud’s daughter, Melissa, is milking. Mornings on a dairy farm are by no means an idle scene but even so, Melissa seems to be on fast-forward. She darts between each cow, leans her back on their right hind leg and reaches under to clean the teats, first with a hydrogen peroxide dip, then with a paper towel. She talks fast too, head bobbing as she tells me of the time she floated down the Connecticut River with her dog on a styrofoam raft. Spud doesn’t milk much these days, maybe once or twice a week. In five years, he’ll sell the farm to one of his workers, build a house on the hill behind his barn, and then he won’t milk at all. He’ll be 72.

“I gotta go to the store, get a coffee,” Spud says. “Wanna go? It’s a ritual I do every morning.” On the way, Spud points out all the dairies. That farm sold out. That one’s “in debt up to their ass.” I look out the window and see seamless pasture and hay fields, as though the landscape had sewn up its wounds. But what really happens is this: the scars of a faltering dairy economy are slow to emerge or will perhaps never show at all. Fields are folded into new, ballooning, patterns of ownership, and the barns still stand tall in them as carcasses, the stanchions inside rocking empty on their chains.

(Westfield, VT | August 2019)

Pat Bresnahan empties his tool bag. Cordless drill: yellow. Hammer: lime green. Power saw: green, too, with a laser to guide the cut. “I’m good with colors,” Pat says. Without them, Pat can’t find his tools. Standing a few feet away, he sees just my eyes and nose, as though he were looking through a long pipe. It’s his right eye that sees. Some days, he can’t see at all.

We see with the back of our heads; that’s where the visual cortex lives. Ten-odd winters ago, Pat is driving up a hill, sticking his neck out to see further up the incline. A boy, 18, in his father’s pickup, slides into the other lane to pass, skids on a patch of ice going 70. The pickup rams into the back of Pat’s car. Pat’s head whips backwards.

“They like me for experimenting,” Pat says. He means the doctors and techies that shuttle him across the country for tests and to try out new toys. “It’s something to do. Otherwise, you’re stuck in a house. Most blind people are stuck in there.” Earlier, he shows me his bionic eye, a camera, housed in a plastic shell, about the length of a finger. He points it at me; “a young woman is in front of you,” a robotic voice reads into his ear.

“I have a lot of skills. The problem is, you can’t go back – I had to go on Social Security, I have a VA pension and I try to make money when I can but for the most part, society isn’t good for blind people. They’re all afraid of us. They are.” Pat speaks without pause, letting each sentence drop as though he’s filling me in on a secret with the end of every phrase. He paces in a tight semi-circle around me, getting a better read of my face, and tells me about how he has taken it upon himself to sue Vermont towns for poor accessibility. “They don’t know who I am. But I’m a blind guy. And when I talk, everybody listens.” He laughs, suddenly, a high-pitched giggle.

But today, he is fixing somebody’s porch. The wood underneath the house is rotting. The porch roof slouches on both sides. I ask him how old the house is. He eyes the black roof shingles, the window frames painted green, the white siding. 1860s, he guesses.

(Westfield, VT | October 2019)

The sign outside reads, in black letters on cold-white light, MOTHER’S DAY SUNDAY PRETTY FLOWERS HERE. Inside, by the counter: two bouquets of purple and white daisies. The store is empty. I wander between the low-slung shelves of Chex Mix and gas station gummy worms, peer through the glass refrigerator doors. A can of coffee, I decide, for the long drive home. When I turn around, it takes a moment to register her as foreground, her grey hair and pale skin seemingly woven into the fabric of the store. “Welcome to Pride,” she says.

It’s a hoarse melody that she sings to customers, low-pitched with bloated vowels. She’s from Maine, moved here fifteen years ago with her daughter and son to be close to her mother. “It backfired,” she says. Her mother has returned to her home state, with the “favorite”, her sister, the youngest in the family. It may have been a blessing. “We decided a while ago that we would only have positive energy in our lives.” We: Lori, her daughter, her son. He will graduate from high school at the end of spring. Last year, he was failing.

“It’s my Friday today,” Lori says on this early Thursday morning. Customers stream in; cool midnight air pools around my ankles. “My dear,” she bellows after each of them. “Welcome to Pride!” A woman on the phone glances over her shoulder and says, “Thank you.” Lori laughs. She will be back here at ten o’clock on Saturday night, work until the minutes bleed into Mother’s Day Sunday. She shares that shift every week with her daughter. Pride is good to her, she says. “They give me 40 hours a week. How many places give you that?”

(Northampton, MA | May 2019)

I learned of Toronto’s network of ravines a few months ago, more than a decade since I left my childhood there behind. The knowledge felt like a whisper, a secret tangle of limbs unfolding beneath my feet. The city in my mind had been a place of positive relief: skyscrapers, squat houses, roadside curbs, the lip of manhole covers. Concrete smooths terrain.

Of course, the ravines were no secret at all. In the summers, when the riverbanks are smeared with fuchsia and violet—milkweed and lupine in full bloom—people descend into the network to catch a wisp of cooler air. The winters here are silent, save for the sound of boots on crumbs of ice, and a teal river slipping slowly around fallen trunks and along the banks, now brown and barren. I, too, had played in these ravines before my family left when I was nine. But a child’s memory is placeless, a scatter of faded inkblots without meridians or a compass. This is what I do remember: plucking a red-brown burr off the matted back of a dog on an autumn afternoon. I remember sliding down the hill on my hand-me-down bicycle with the dinosaur on it, elbows and knees wrapped in padding. I remember I was scared, and I remember my father at the bottom with his arms spread to catch me. But I did not remember this negative topography, and I felt so small and wonderful imagining this land carved out over millennia to be here so effortlessly in front of me, as though somebody had merely dragged their finger along a flat bed of wet sand.

I returned here at the beginning of this year. I wandered with my head tilted toward these branches. Follow the sinuous lines and you’ll see them interrupted: birds nests, a red cardinal. I smile at every passerby, hoping foolishly that somebody would recognize me, and know that I have come home, but nobody does and they are strangers to me, too.

(Toronto, ON | January 2020)

There is an old woman who hides aluminium cans in these bushes. On the day that I saw her, she was wearing the uniform of the elderly. A polyester blouse patterned with shapeless spots of muted purples and plums hung loose on her concave frame, all its buttons, up to the last at the collar, done up. She wore dark grey trousers that fell without a crease to her ankles. Her hair, grey with a few black strands, was pinned back with a barette. It was the end of summer; four hundred meters away on the shoreline of Victoria Harbor, ocean winds were tinged with a lingering coolness. But where I was on Queen’s Road, mid-nineteenth century apartment buildings left only a blue sliver of sky above, and the still air clung to the bare limbs of passersby.

A man with dark brown skin and a thick head of gel-hardened black hair sat on a bench and ate his dinner. Porcelain bowl, metal spoon. Before long, he was joined by others, who brought with them tall cans of Blue Girl. The sun creeped west; shadows cast by bamboo scaffolding and overhanging store signs stretched thin across pavement. The old woman shuffled toward the bench, and not speaking the same language as the men, gestured at their cans of beer. One man offered his half-empty can. She emptied it into the soil of a potted tree standing tall nearby. And then, gripping the can in her arthritic fingers, she walked toward these plants and gently placed it at the base of the stems so that it was hidden away in the leaves’ shadows. She turned back to continue down the street.

Before she went far, the man who came first with the dinner, now having mostly finished his beer, rapped the base of the can on the bench in twos.

Pang pang.

Pang pang.

Pang pang.

The woman pivoted and came to him, took the can and once again dribbled what was left of it in the soil. The beer pooled on the surface for a moment, and then disappeared into soil's air pockets, the last drips leaving soft craters in the dirt. She carried the can, like the first, toward these plants here, but before she could walk more than ten paces, a grape Fanta can tumbled hollowly across the pavement toward her heels. The woman turned around again, dragged her feet and, without looking up at who threw it, picked the can up, and came back toward these plants. The thrower, a man who had been sitting a few meters away on the steps of the subway station, watched her go. The woman laid the cans, one purple, one beige, in the shadows.

She disappeared down the street, and then returned later when the low evening sun had begun to paint passing faces in golden light. She was pulling a small folding trolley stacked high with teetering cardboard boxes. These days, cardboard in Hong Kong goes for half a dollar a pound. She bent over to see where she had hidden the cans, reached her swollen fingers under this canopy. Then she balanced the cans one by one on top of her cardboard pile, turned to watch for a gap in traffic, and shuffled across the road.

(Hong Kong, August 2018)